Charlotte Police Help Decrease Robberies Agains Hispanics in Apartment Complex

Neighborhoods and Vehement Law-breaking

Highlights

- Rates of violent crime in the The states have declined significantly over the past two decades, only disparities persist.

- Exposure to vehement crime damages the health and development of victims, family unit members, and entire communities. Low-income people and racial and ethnic minorities are unduly affected.

- Violent crime is geographically full-bodied in particular neighborhoods and in more localized areas known equally hot spots; evidence suggests that problem-oriented policing of hot spots can be effective.

- Strong social system, youth job opportunities, immigration, and residential stability are amongst several neighborhood characteristics associated with lower crime rates.

Source: Federal Bureau of Investigation. "Crime in the United States by Volume and Rate per 100,000 Inhabitants, 1995–2014" (ucr.fbi.gov/criminal offense-in-the-u.s/2014/crime-in-the-u.s.-2014/tables/table-ane)). Accessed seven August 2016.

Violent criminal offence wreaks a terrible touch on not just on private victims, their families, and friends but also on nearby residents and the fabric of their neighborhoods.1 Exposure to vehement law-breaking can damage people'southward health and development,two and violence can push communities into vicious circles of decay. Rates of violent crime in the U.s.a. have declined significantly over the past 20 years. Disadvantaged neighborhoods have experienced larger drops in crime, although significant disparities persist.

Violent crime also has a uniquely powerful role in defining neighborhoods. A study of neighborhoods in 22 cities indicates that levels of violent criminal offense in a neighborhood, particularly robbery and aggravated assail, strongly predict residents' perceptions of offense, whereas property criminal offense has piffling upshot.iii An assortment of studies too suggest that trigger-happy crime reduces neighborhood holding values more than property crime does.four Perceptions likewise differ among groups. Residents with children and longer-term residents, for instance, consistently perceive greater levels of criminal offense and disorder than practise their neighbors.5 Decisions on where to move often reflect concerns about safety. People with housing selection vouchers, for example, consistently rate a safer neighborhood as their top priority.half-dozen

Variations in levels of violent crime are linked to complex characteristics of neighborhoods, including disadvantage, segregation, land use, social control, social capital, and social trust, as well equally the characteristics of nearby neighborhoods. Identifying the root causes of trigger-happy criminal offence can also point to promising strategies to reduce its incidence and impact.

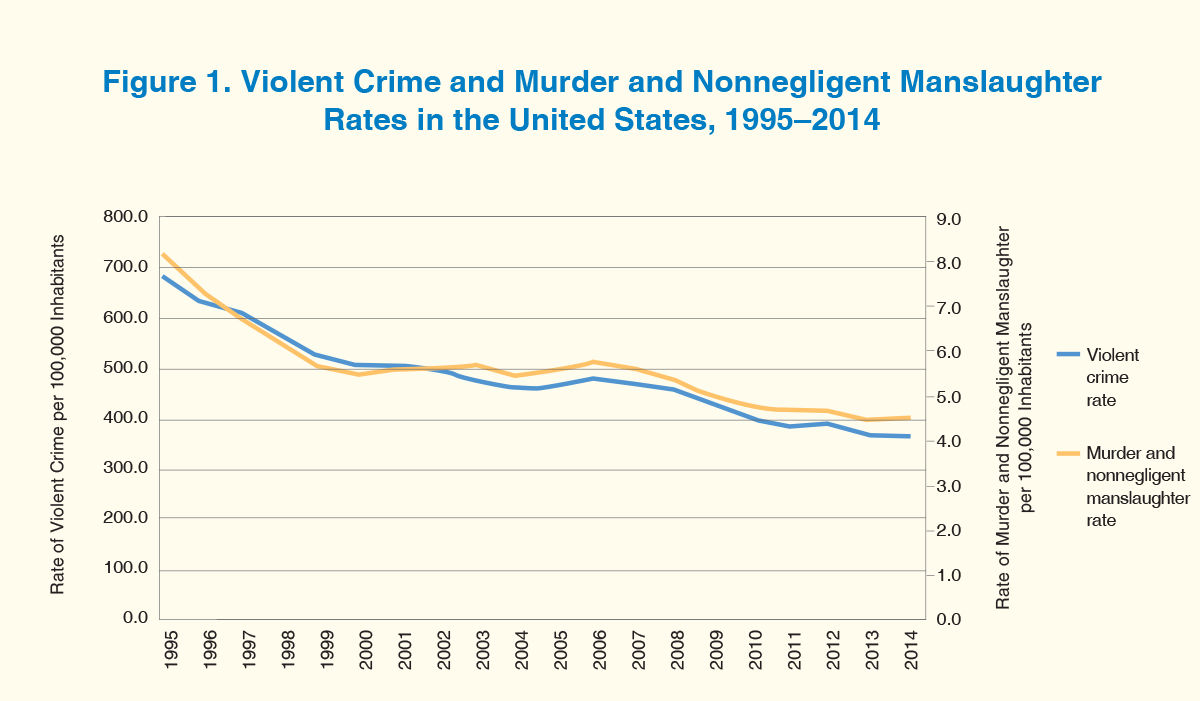

There are three major national sources of crime data in the U.s.: the Federal Bureau of Investigation'due south Uniform Criminal offense Reports, which reports data on crime counts, crime rates, and arrests; the National Crime Victimization Survey, which tracks self-reported victimizations of crime; and the National Vital Statistics Organization, which has data on deaths, including homicides.7 At the national level, these sources betoken a massive decline in violent crime — generally defined to include murder, rape, robbery, and aggravated assault — over the past twenty years.eight According to the Uniform Crime Reports, the violent criminal offence charge per unit dropped by almost half between 1995 and 2014, from 684.five violent crimes per 100,000 inhabitants to 365.v (fig. 1).nine The homicide charge per unit also dropped by nearly one-half over the same period, from 8.2 per 100,000 inhabitants to 4.5.10 And according to the National Criminal offence Victimization Survey, by 2014, the tearing victimization rate — that is, the rate at which people are victims of violent crime — dropped to 20.i per 1,000 persons, only about a quarter of 1993's rate of 79.8.11 Compared to other wealthy nations, modern rates of violent crime in the United States are not exceptional, though homicide rates remain "probably the highest in the Western globe."12 In detail, gun violence is far more common in the U.S. than in other Western nations.13

Source: Jennifer Fifty. Truman and Lynn Langton. 2015. "Criminal Victimization, 2014," Agency of Justice Statistics.

No consensus exists on a single cause for the massive American refuse in crime. In 2015, the Brennan Eye for Justice reviewed testify on theories to explain the reject, finding that such factors every bit an crumbling population, consumer confidence, decreased alcohol consumption, income growth, increased rates of incarceration, and increased policing all likely contributed.14 With regard to increased incarceration, the National Academy of Sciences' 2012 report ended that although higher incarceration rates may take acquired a decline in crime, "the magnitude of the reduction is highly uncertain and the results of most studies suggest information technology was unlikely to be accept been large," and, moreover, that high incarceration rates had significant social costs, particularly for minority communities.15

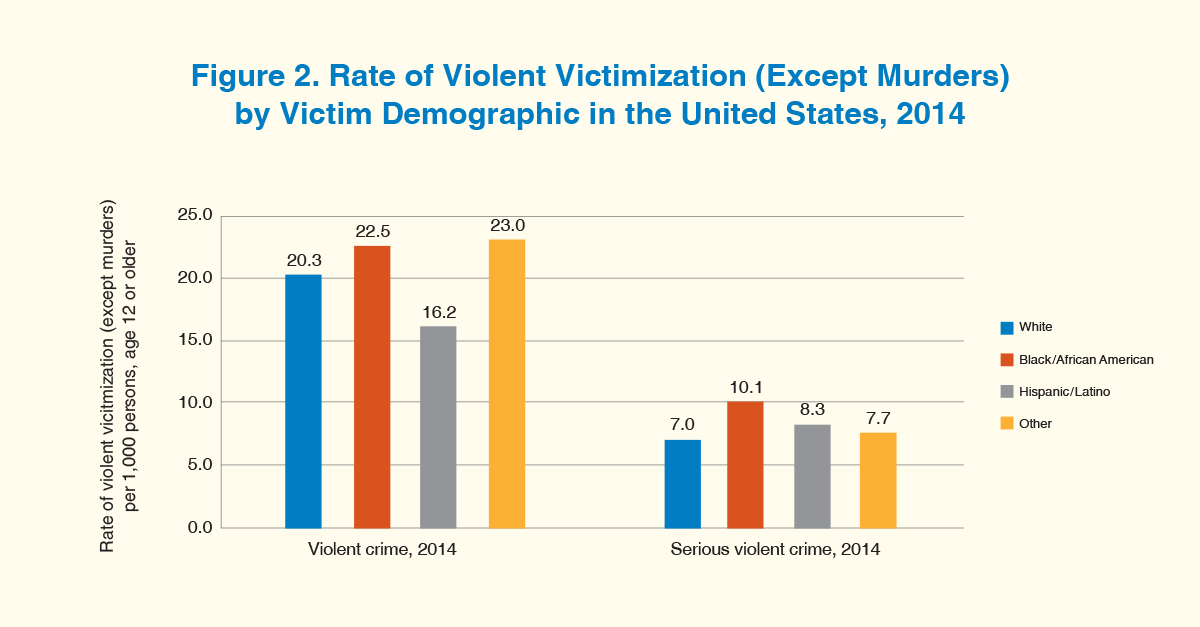

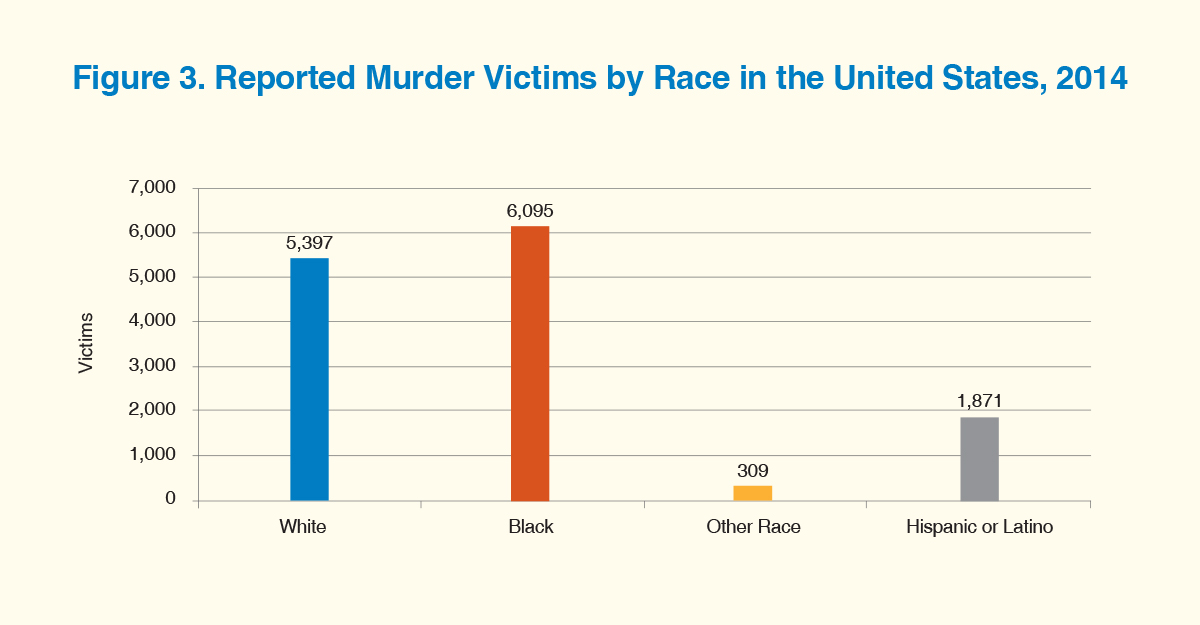

At the same time, African Americans and Hispanics are more likely to be victims of trigger-happy crimes — especially serious trigger-happy crimes — than are whites, although the gap has narrowed over the by 10 years (fig. ii).sixteen African Americans are disproportionately victims of homicide compared with whites or Hispanics (fig. 3).17 Similarly, low-income people are much more likely than others to experience crime, including violent crime.eighteen

Although evidence indicates that neighborhood characteristics contribute to these disparities, none of the major national sources of crime data provide comprehensive information at the neighborhood level. Researchers ordinarily ascertain neighborhoods according to census tracts, which include from 1,200 to 8,000 people and are drawn to reflect visible community boundaries.19 The absence of almanac, national neighborhood-level data frustrates efforts to compare vehement crime trends beyond and within communities.

One particularly expansive national source for neighborhood-level crime data is the National Neighborhood Crime Written report (NNCS), which collects street crime data reported to police force for the year 2000 from 9,593 nationally representative neighborhoods in 91 large cities.twenty Considering NNCS information, Peterson and Krivo establish hitting racial inequality beyond neighborhoods in the boilerplate rates of violent crime: predominantly African-American neighborhoods (those that consist of more than seventy% African-American residents) averaged five times as many violent crimes as predominantly white communities; predominantly Latino neighborhoods averaged most two and a half times equally many violent crimes equally predominantly white neighborhoods. These differences in crime rates are linked to structural disparities: segregated neighborhoods also tend to be disadvantaged and lack access to community resource, institutions, and means of social control such every bit effective policing as well as social trust.21 A followup study is underway to add data from 2010 and clarify trends.22

Disadvantaged, segregated communities have experienced a big portion of the national reject in vehement crime simply remain disproportionally affected by high violent crime rates. In 2015, Friedson and Sharkey considered neighborhood-level violent crime in half-dozen cities — Chicago; Cleveland; Denver; Philadelphia; Seattle; and St. Petersburg, Florida — over the by decade or longer.23 In each of these cities, the absolute rate of violent crime in the virtually violent neighborhoods dropped dramatically: in Cleveland, for example, the absolute difference in violent crime between the most violent 5th of neighborhoods and all the rest declined by 65 pct. Similarly, poor neighborhoods, majority African-American, and majority Hispanic neighborhoods narrowed the gap between them and other neighborhoods. Just although overall trigger-happy criminal offense rates have declined substantially, the distribution of violent offense remains near the same: the communities that were initially the near violent generally remained the nigh violent. In all six cities, the most violent fifth of neighborhoods nonetheless experienced more tearing crime than the 2d most trigger-happy fifth of neighborhoods experienced before the decline.

Similarly, Lens et al. found that in vii big American cities, housing pick voucher holders' exposure to neighborhood crime declined essentially from 1998 to 2008. This decline happened not because voucher holders moved to areas with lower crime rates only because their neighborhoods' crime rates improved more those of other neighborhoods (although these neighborhoods however lagged behind on absolute levels of crime).24

Within neighborhoods, research has indicated that tearing criminal offence occurs in a small number of "hot spots."25 These hot spots are "micro places" — either street intersections or segments (two cake faces on both sides of a street between ii intersections).26 One written report reviewed Boston police records from 1980 through 2008 and found that fewer than 3 percent of micro places deemed for more than than half of all gun violence incidents.27 When gun violence increases, these hot spots business relationship for well-nigh of the increment, and the same occurs when gun violence declines. Hot spots' presence is linked to both opportunity — for instance, the presence of more charabanc stops, a busy street, or the lack of street lighting — and social controls on criminal offence.28 Both informal social controls, such as commonage efficacy, and formal social controls, such as the presence of law enforcement, could prevent hot spots.29 Evidence suggests that policing aimed at hot spots — particularly problem-oriented policing that focuses on specific problems such as gun seizures and engages the community as a partner — can be more effective and does non just displace crime.30

Much trigger-happy crime may besides occur within narrow social networks.31 In general, a asymmetric number of murder victims and offenders are young,32 and nigh 4-fifths of victims33 and three-fifths of offenders34 are male person. As well, many studies take observed "victim-offender overlap," meaning that the victims and offenders of violent crime are often members of the aforementioned social network, and neighborhood context such equally street culture might influence this phenomenon.35 1 study found that in Boston, about 85 percentage of gunshot injuries occur within a single network of people representing less than 6 percent of the city's full population.36 Drawing on an array of research on networks, Papachristos argues that "gun violence is transmitted through particular types of risky behaviors (such as engaging in criminal activities) and is related to the ways in which peculiarly pathogens (e.thousand. guns) move through networks."37 Every bit Sampson notes, networks can enable prosocial activities as well as gangs and crime.38

Neighborhoods' incidence of violent crime is related to an array of intertwined characteristics, including poverty, segregation, and inequality; collective efficacy, disorder, trust, and institutions; job access; immigration; residential instability, foreclosures, vacancy rates, and evictions; land utilize and the built surround; neighborhood change; and location of housing assistance. These characteristics can be both the crusade and outcome of violent criminal offense.39 Neighborhoods modify dynamically: violence tin can influence people to exit, which leads to an increase in segregation and violence.forty Moreover, neighborhoods are affected not only by their ain internal characteristics simply also by those of nearby neighborhoods. After decision-making for neighborhoods' own internal characteristics, rates of violence in Chicago neighborhoods are significantly and positively linked to those of surrounding neighborhoods.41

Poverty, Segregation, and Inequality.

Neighborhoods with more full-bodied disadvantage tend to experience higher levels of violent offense. Numerous studies, for example, bear witness that neighborhoods with college poverty rates tend to take higher rates of violent law-breaking.42 Greater overall income inequality inside a neighborhood is associated with higher rates of criminal offense, especially violent offense.43 Sampson notes that even though the city of Stockholm has far less violence, segregation, and inequality than the metropolis of Chicago, in both cities a disproportionate number of homicides occur in a very small number of very disadvantaged neighborhoods.44

Racially and ethnically segregated neighborhoods also tend to have higher rates of trigger-happy crime. Peterson and Krivo"due south analysis of nationwide neighborhood crime data for the twelvemonth 2000 demonstrates, notwithstanding, that vehement crime rates in predominantly African-American and Latino neighborhoods differ footling from predominantly white neighborhoods afterward controlling for segregation and disadvantage. In particular, spatial disadvantage — that is, adverse characteristics such as poverty or criminal offence amongst nearby neighborhoods — appears to bulldoze disparities in local crime rates betwixt these neighborhoods.45 Equally Pattillo-McCoy writes, crime from disadvantaged areas in Chicago often spills over into middle-form, predominantly African-American neighborhoods.46 Moreover, the effects of citywide segregation extend across majority-minority neighborhoods: neighborhoods nationwide, regardless of their racial composition, tend to experience higher rates of trigger-happy law-breaking when they are located in cities with higher levels of segregation.47

Poverty, segregation, and inequality are related to neighborhoods' access to resource and ability to solve bug, including problems that foster crime.48 These resources include access to institutions, particularly effective customs policing and the swift prosecution of violent offense. In 2015"due south Ghettoside, Leovy explores how underpolicing of vehement crime spurred high homicide rates in segregated S Central Los Angeles neighborhoods as an alternate "ghettoside" police emerged.49 This alternate police force involves witnesses scared to evidence, the formation of gangs for protection, and cascades of disputes and violent offense among interwoven communities.50 Equally Massey writes, "In a niche of violence, respect tin but be built and maintained through the strategic utilise of force."51 Evidence suggests that a greater propensity for arguments to escalate to lethal violence, combined with easier access to firearms, contributes to higher rates of homicide in the United states of america.52 Every bit Leovy points out, the absenteeism of law has fostered violent criminal offence in communities throughout history.53

Source: Federal Bureau of Investigation. "Murder Victims by Race, Ethnicity, and Sex, 2014" (ucr.fbi.gov/crime-in-the-u.s/2014/criminal offense-in-the-u.south.-2014/tables/expanded-homicide-information/expanded_homicide_data_table_1_murder_victims_by_race_ethnicity_and_sex_2014.xls). Accessed vii August 2016.

In many communities of color, troubled relationships with police enforcement — linked to aggressive tactics and the disproportionate prosecution of drug crimes — hinder efforts to accost violent criminal offence.54 Full-bodied disadvantage, crime, and imprisonment appear to collaborate in a continually destabilizing feedback loop.55 In disadvantaged, segregated neighborhoods, residents may also exist more probable to be detached from social institutions and disregard the police force,56 hampering criminal offence enforcement and prevention.57 Evidence suggests that community policing can improve communities' relationships with police enforcement and contribute to strategies such every bit hot-spot policing that seem to reduce trigger-happy crime.58

Commonage Efficacy, Disorder, Trust, and Institutions. Commonage efficacy, defined every bit social cohesion among neighbors and their willingness to intervene on behalf of the common expert, appears to be an important determinant of violent crime in neighborhoods.59 Social cohesion measures enquire, for case, whether residents believe people in their neighborhood can be trusted.threescore Beyond neighborhoods in Chicago and cities worldwide, Sampson and others have found that collective efficacy and violent crime are interrelated: violence tin can reduce collective efficacy, and collective efficacy can prevent future trigger-happy crime.61

Collective efficacy can affect youths' "street efficacy," their perceived ability to avoid trigger-happy confrontations and observe ways to be safety in their own neighborhood, in turn influencing their likelihood to turn to violence. Later on controlling for individual and family factors, Sharkey plant that Chicago youth who alive in neighborhoods with concentrated disadvantage and depression collective efficacy have lower street efficacy, and those with higher street efficacy are less likely to resort to violence or associate with runaway peers. Every bit Sharkey writes, in communities with lower collective efficacy where "residents retreat from public life and treat the presence of violence with resignation, adolescents may feel that attempts to avoid violence are futile, and that they are on their own in their attempts to exercise so."62

Commonage efficacy is linked to disorder, such every bit garbage in the streets or broken windows.63 Sampson notes that people's perceptions of disorder in their neighborhood are likely related to collective senses of social meaning and inequality.64 "Broken windows" policing, aimed at reducing perceived disorder to foreclose offense, is one of the most influential philosophies in policing. Rigorous research suggests that disorder, however, might ultimately be a product of root causes such as the concentration of disadvantage and low collective efficacy, which also lead to crime.65 Disorder tin trigger reactions that farther increment disadvantage and criminal offense — for example, by encouraging people to move and stigmatizing a neighborhood.66 In fact, strong show indicates that shared perceptions of by disorder (that is, what people thought about a neighborhood years ago) are a meliorate predictor of homicides in neighborhoods than are present levels of physical disorder.67

Ane study of trigger-happy law-breaking in Chicago neighborhoods during the 1990s found that legal cynicism — when people view the law as "illegitimate, unresponsive, and ill equipped to ensure public condom" — explained why homicide persisted in some communities despite citywide declines in poverty and violence.68 Kirk and Papachristos advise that legal cynicism is linked to ii related influences: neighborhood structural conditions and constabulary practices and interaction with neighborhood residents.69 Strong social organization, still, tin can reduce vehement crime. Sampson constitute that Chicago neighborhoods with more than connected leadership, as demonstrated by social ties between leaders, tend to have much lower homicide rates even controlling for factors such as concentrated disadvantage.70

In some circumstances, vacant and foreclosed properties are associated with increased neighborhood crime rates.

Job Admission. Job access tin can assist explain variations in law-breaking types beyond urban neighborhoods. One study of Atlanta in the early on 1990s examined job opportunity for youth in neighborhoods, including whether jobs were geographically attainable, whether youth would be qualified to hold them, and the level of contest for those jobs. This study establish that poor chore opportunity was closely linked with neighborhood-level law-breaking, although more closely to property crime than fierce crime.71

Immigration. Numerous studies show that clearing is strongly associated with lower rates of fierce crime.72 1 rigorous report of neighborhoods in Los Angeles in the mid-2000s, for case, found that greater concentrations of immigrants in a neighborhood are related to pregnant drops in crime.73 Similarly, Sampson, in analyzing data on Chicago neighborhoods, found that, after controlling for other factors, concentrated clearing is direct associated with lower rates of violence.74 One reason for this finding might be that people who immigrate accept characteristics that make them less probable to commit crimes — for example, motivation to piece of work and appetite.75 Leovy, because Los Angeles, notes, "Despite their relative poverty, recent immigrants tend to take lower homicide rates than resident Hispanics and their descendants born in the United States. This is considering homicide flares among people who are trapped and economically interdependent, not among people who are highly mobile."76

Residential Instability, Foreclosures, Vacancy Rates, and Evictions. Residential instability — that is, more frequent moves amidst a neighborhood's residents — appears in some circumstances to exist related to increases in violent law-breaking.77 Research shows that residential instability might touch violence at to the lowest degree in part by, for instance, reducing customs efficacy.78 Violent crime and residential instability appear to be interrelated: i study considering Los Angeles neighborhoods in the mid-1990s estimated that the effect of vehement crime on instability was twice as strong as that of instability on law-breaking.79

Multiple studies have found that foreclosures increase violent law-breaking on nearby blocks.eighty One written report notes that because foreclosures announced to pull crimes indoors, where offenders are less likely to be caught, crimes resulting from foreclosures and subsequent vacant units could be underreported.81 On the other hand, foreclosures might merely reshuffle crime at the local level.82

Vacancies and evictions can as well lead to tearing law-breaking by destabilizing communities and creating venues for criminal offense. A study of Pittsburgh found that violent criminal offence increased past 19 percent within 250 feet of a newly vacant foreclosed home and that the crime rate increased the longer the holding remained vacant.83 In 2016's Evicted, Desmond notes that Milwaukee neighborhoods in the mid-2000s with loftier eviction rates had higher vehement crime rates the following year after decision-making for factors including past crime rates.84 Desmond suggests that eviction affects crime by frustrating the relationship among neighbors and preventing the evolution of community efficacy that could prevent violence.85

Land Use and the Congenital Surround. In The Expiry and Life of Great American Cities, Jane Jacobs proposes several elements that could make neighborhoods safe, such as a clear demarcation betwixt public and individual space; "eyes on the street," such equally nearby shops; and fairly continuous use.86 Some empirical inquiry, however, suggests that mixed-use areas, which combine commercial and residential properties, take lower rates of crime than practise commercial-only areas, perhaps by reducing crimes of opportunity.87 Other land employ strategies might too reduce violent crime. A study of a natural experiment in Youngstown, Ohio, which cleaned up vacant lots and funded efforts to better them, found that community improvement of lots reduced vehement crime nearby (meet "Housing, Inclusion, and Public Condom").88

Neighborhood Change. Changes in neighborhood demographics, such as gentrification, can bear on violent crime rates. Kirk and Laub suggest that gentrification tin can cause an initial increase in crime because neighborhood change causes destabilization, although in the long run gentrification leads to a pass up in crime as neighborhood cohesion increases.89 Neighborhoods' spatial location can also bear on offense rates. Boggess and Hipp found that in Los Angeles in the 1990s, neighborhoods at the "frontier" of gentrification had many more than aggravated assaults than did those located near other neighborhoods also experiencing gentrification.xc Prove also indicates that the general decline in crime may have contributed to gentrification, as higher-income families feel more comfortable moving into the city.91

Replacing distressed public housing with new mixed-income housing through the Promise Vi program decreased violent law-breaking rates in certain neighborhoods.

Location of Housing Assistance. Rigorous research to date demonstrates that violent crime generally does not increase in neighborhoods when households with housing vouchers move in. In 2008, an commodity in The Atlantic suggested that in Nashville, Tennessee, significant neighborhood-level increases in tearing offense were linked to voucher holders' moves.92 Ellen et al. analyzed neighborhood-level criminal offense in 10 large American cities from 1995 to 2008, even so, and establish little show that households with housing pick vouchers acquired offense to increase where they moved. Instead, they plant strong prove indicating that voucher holders tend to move into neighborhoods where law-breaking is already increasing, perchance seeking more affordable rents.93 Some other studies propose that associations betwixt increases of voucher holders and increases in offense could be limited to disadvantaged neighborhoods or neighborhoods where households receiving housing assistance are full-bodied.94 Mast and Wilson considered this question in Charlotte-Mecklenburg County, N Carolina, from 2000 to 2009, finding that increases in voucher holders were associated with criminal offense increases simply in neighborhoods that exceed relatively high thresholds for poverty or concentration of voucher holders.95

Public housing sabotage also appears to accept afflicted neighborhood trigger-happy crime rates. From the cease of the 1990s through the mid-2000s, public housing developments across the nation were demolished through the HOPE VI program, forcing thousands of families to relocate with housing vouchers.96 Looking at criminal offence rates in Atlanta and Chicago, Popkin et al. found that in Atlanta and Chicago, crime rates plummeted in the neighborhoods where public housing had been demolished alongside net decreases citywide; in Chicago, they estimated that the decrease in vehement crime in those areas was more than sixty per centum greater than it would accept been without Hope 6. Many of these public housing developments were severely distressed with high rates of violent crime, and HOPE VI'due south combination of sabotage and new mixed-income housing appears to accept reduced crime in these neighborhoods.97 Moreover, most neighborhoods also absorbed households with relocation vouchers without whatsoever effect on law-breaking rates. The neighborhoods that saw significant increases in law-breaking with the addition of voucher holders were those that already had high rates of poverty and crime.98

Violent crime has numerous, lasting effects on neighborhood residents that extend beyond its direct bear upon on victims and their families and friends. One of the most significant findings from the Moving to Opportunity experiment, which enabled low-income families to move to low-poverty neighborhoods, was the outcome on movers' wellness. Movers ended upward in much safer neighborhoods, and parents and adolescent girls experienced significant improvements in health, including lower rates of obesity, linked to reductions in stress.99 In unsafe areas, people may avoid going exterior, and a strong human relationship exists between perceived neighborhood safety and obesity rates.100

In full general, exposure to violence puts youth at significant risk for psychological, social, academic, and concrete challenges and also makes them more likely to commit violence themselves.101 Exposure to gun violence can desensitize children, increasing the likelihood that they deed violently in the future.102 One study institute that children exposed to an incident of tearing crime scored much lower on exams a week afterward.103 Some other study focusing on Chicago in the 2000s considered children's exposure to neighborhood violence over time, finding that, afterwards controlling for differences betwixt students, children living in more than trigger-happy neighborhoods fall farther behind their peers in schoolhouse as they grow older and that this result is similar in size to that of socioeconomic disadvantage.104 At a larger level, Chetty and Hendren detect that children who alive in neighborhoods with higher criminal offense rates for 20 years experience significant reductions in income every bit adults.105

Neighborhoods of concentrated poverty and disadvantage tin can also create coercive sexual environments in which sexual harassment, molestation, exploitation, and violence against women and girls get accepted. These environments, which unduly affect adolescents of colour, negatively bear upon children's sexual evolution and tin can lead to long-term psychological stress and substance corruption.106

The evidence on neighborhoods and trigger-happy crime suggests several strategies for improving safe and neighborhood health. Investing in communities caught in cycles of crime, decay, and disinvestment can assistance reduce crime rates.107 Research on social ties and institutions suggests that strong community organizations and leadership tin can brand a departure. Investments that increment inclusion and back up education, skills, and access to jobs may exist necessary to address the full-bodied disadvantage at the root of violent law-breaking in neighborhoods. Housing programs may avert reconcentrating poverty in disadvantaged areas and crossing thresholds linked to increases in vehement criminal offense. In full general, policies that reduce economic, racial, and ethnic segregation can increase communities' access to key resource to preclude fierce criminal offense and promote healthy development. In addition, more comprehensive national data on law-breaking at the neighborhood level can aid us better understand trends.

Promising programs could too forbid violent criminal offense by helping youth and others avoid violence. The Becoming a Man programme in Chicago, for case, adopts cerebral behavioral therapy to assist young men slow downwards their thinking and consider whether their automatic thoughts fit the situation. New rigorous experimental evidence suggests that the program tin reduce violent crime arrests by 45 to 50 percent and improve graduation rates by 12 to nineteen pct.108

To a large extent, changes in vehement crime are linked to broader social progress and economic gains. Today, equally Friedson and Sharkey point out, the recent decline of violent offense offers opportunities for "a virtuous cycle of failing crime and disorder, reinvestment, and greater integration of disadvantaged neighborhoods into the urban social textile."109 Taking advantage of these possibilities could reduce disparities and save more people, families, and neighborhoods from the affect of fierce crime.

— Chase Sackett, Former HUD Staff

- Patrick Sharkey and Robert J. Sampson. 2015. "Violence, Noesis, and Neighborhood Inequality in America," in Social Neuroscience: Brain, Mind, and Gild, Russell Schutt, Matcheri S. Keshavan, and Larry J. Seidman, eds. Cambridge: Harvard University Printing.

- E.g., David J. Hardin. 2009. "Collateral Consequences of Violence in Disadvantaged Neighborhoods," Social Forces 88:two, 757–84.

- John R. Hipp. 2010. "Assessing Crime as a Trouble: The Relationship between Residents' Perception of Law-breaking and Official Offense Rates over 25 Years," Crime & Delinquency 59:4, 616–48.

- E.g., John R. Hipp, George East. Tita, and Robert T. Greenbaum. 2009. "Drive-bys and Merchandise-ups: Examining the Directionality of the Offense and Residential Instability Human relationship," Social Forces 84:4, 1777–812. For a summary of research on this topic, encounter David Kirk and John Laub. 2010. "Neighborhood Modify and Crime in the Modern Metropolis, Crime and Justice: A Review of Enquiry 39, 441–502.

- John R. Hipp. 2010. "Resident perceptions of offense: How much is 'bias' and how much is micro-neighborhood outcome?" Criminology 48:2, 475–508.

- Run into, east.1000., Lenore Healy and Michael Lepley. 2016. "Housing Voucher Mobility in Cuyahoga County," Housing Inquiry and Advancement Middle.

- The University of Chicago Criminal offense Lab. "Data on Crime Patterns" (crimelab.uchicago.edu/folio/crime-patterns). Accessed 19 July 2016.

- See Federal Bureau of Investigation. "Crime in the United States past Volume and Rate per 100,000 Inhabitants, 1995-2014" (ucr.fbi.gov/crime-in-the-u.s/2014/crime-in-the-u.s.-2014/tables/table-1). Accessed 15 August 2016.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Jennifer Fifty. Truman and Lynn Langton. 2015. "Criminal Victimization, 2014," Agency of Justice Statistics.

- James P. Lynch and William Alex Pridemore. 2011. "Crime in International Perspective," in Law-breaking and Public Policy, James Q. Wilson and Joan Petersilia, eds. New York: Oxford Academy Printing, 1–52, 24.

- Kevin Quealy and Margot Sanger-Katz. 2016. "Compare These Gun Death Rates: The U.S. Is in a Dissimilar Earth," New York Times, June xiii.

- Oliver Roeder, Lauren-Brooke Eisen, and Julia Bowling. 2015. "What Caused the Crime Decline?" Brennan Center for Justice.

- National Academy of Sciences. 2012. The Growth of Incarceration in the United States: Exploring Causes and Consequences, Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 4.

- Truman and Langton, 9. Serious vehement criminal offense in the NCVS includes rape or sexual assault, robbery, and aggravated assault.

- Federal Bureau of Investigation. "Murder Victims past Race, Ethnicity, and Sex activity, 2014" (ucr.fbi.gov/crime-in-the-u.s.-2014/tables/expanded_homicide_data_table_1_murder_victims_by_race_ethnicity_and_sex_2014.xls). Accessed fifteen August 2016

- Melissa S. Kearney, Benjamin H. Harris, Elisa Jacome, and Lucie Parker. 2014. "Ten Economic Facts about Crime and Incarceration in the United states," The Brookings Institution.

- See U.S. Demography Bureau. "How the Demography Bureau Measures Poverty" (www.demography.gov/topics/income-poverty/poverty/guidance/poverty-measures.html). Accessed xvi Baronial 2016.

- Ruth D. Peterson and Lauren J. Krivo. 2010. Divergent Social Worlds: Neighborhood Criminal offence and the Racial-Spatial Split, New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

- Ibid.

- National Scientific discipline Foundation. "Collaborative Research: Offense and Community in a Changing Guild, the National Neighborhood Crime Study 2" (nsf.gov/awardsearch/showAward?AWD_ID=1357207). Accessed 26 July 2016.

- Michael Friedson and Patrick Sharkey. 2015. "Violence and Neighborhood Disadvantage after the Law-breaking Refuse," The Annals of the American University of Political and Social Science 660:1, 341–58.

- Michael C. Lens, Ingrid Gould Ellen, and Katherine O'Regan. 2011. "Neighborhood Law-breaking Exposure Among Housing Option Voucher Households," U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development.

- Anthony A. Braga, Andrew 5. Papachristos, and David M. Hureau. 2009. "The Concentration and Stability of Gun Violence at Micro Places in Boston, 19802008," Periodical of Quantitative Criminology 26:ane, 33–53.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- David Weisburd, Elizabeth R. Groff, and Sue-Ming Yang. 2013. "Agreement and Controlling Hot Spots of Crime: The Importance of Formal and Informal Social Controls," Prevention Scientific discipline 15:i, 31–43.

- Ibid.

- Anthony A. Braga, Andrew Five. Papachristos, and David M. Hureau. 2014. "The Effects of Hot Spots Policing on Criminal offense: An Updated Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis," Justice Quarterly 31:four, 633–63.

- Andrew V. Papachristos. 2014. "The Network Structure of Law-breaking," Sociology Compass 8:4, 347–57.

- Federal Bureau of Investigation. "Murder Victims past Age, Sex activity, Race, and Ethnicity, 2014" (ucr.fbi.gov/law-breaking-in-the-u.s/2014/crime-in-the-u.due south.-2014/tables/expanded-homicide-data/expanded_homicide_data_table_2_murder_victims_by_age_sex_and_race_2014.xls). Accessed fifteen August 2016.

- Federal Agency of Investigation. "Murder Offenders by Race, Ethnicity, and Sex, 2014" (ucr.fbi.gov/crime-in-the-u.s/2014/crime-in-the-u.s.-2014/tables/expanded-homicide-data/expanded_homicide_data_table_3_murder_victims_by_age_sex_and_race_2014.xls). Accessed fifteen Baronial 2016.

- Federal Agency of Investigation. "Murder Victims by Race, Ethnicity, and Sex, 2014."

- Mark T. Berg, Eric A. Stewart, Christopher J. Shreck, and Ronald L. Simons. 2012. "The Victim-Offender Overlap in Context: Examining the Role of Neighborhood Street Civilisation."

- Andrew Five. Papachristos, Anthony A. Braga, and David Thousand. Hureau. 2012. "Social Networks and the Risk of Gunshot Injury," Journal of Urban Health 89:vi, 992–1003. Cited in Papachristos.

- Ibid., 354.

- Sampson 2012. See as well Christopher R. Browning, Seth L. Feinberg, and Robert D. Dietz. 2004. "The Paradox of Social Organization: Networks, Collective Efficacy, and Violent Crime in Urban Neighborhoods," Social Forces 83:ii, 503–34.

- John R. Hipp. 2010. "A Dynamic View of Neighborhoods: The Reciprocal Human relationship between Criminal offense and Neighborhood Structural Characteristics," Social Problems 57:2, 205–xxx.

- Jeffrey D. Morenoff and Robert J. Sampson. 1997. "Trigger-happy Criminal offense and The Spatial Dynamics of Neighborhood Transition: Chicago, 1970-1990," Social Forces 76:1, 31–64.

- Sampson 2012.

- Ibid.

- John R. Hipp. 2007. "Income Inequality, Race, and Identify: Does the Distribution of Race and Class within Neighborhoods Affect Crime Rates?" Criminology 45:3, 665–97.

- Sampson 2012.

- Peterson and Krivo.

- Mary Patillo. 2013. Black Lookout Fences: Privilege and Peril Amidst the Black Eye Class, Chicago: Academy of Chicago Printing. Cited in Peterson and Krivo.

- Danielle Corinne Kuhl, Lauren J. Krivo, and Ruth D. Peterson. 2009. "Segregation, Racial Structure, and Neighborhood Violent Criminal offense,"American Journal of Sociology 114:6, 1765–802.

- Ibid.

- Jill Leovy. 2015. Ghettoside: A True Story of Murder in America, New York: Spiegel & Grau.

- Leovy.

- Douglas Due south. Massey. 1995. "Getting Away with Murder: Segregation and Violent Law-breaking in Urban America," University of Pennsylvania Law Review 143:v, 1203–32, 1221.

- See Franklin E. Zimring and Gordon Hawkins. 1997. Crime Is Not the Trouble: Lethal Violence in America, New York: Oxford University Press.

- Leovy.

- Meet Randall Kennedy. 1998. Race, Criminal offense, and the Law, New York: Random House; Leovy; Michelle Alexander. 2010. The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness, New York: New Press.

- Robert J. Sampson and Charles Loeffler. 2010. "Penalization's Place: The Local Concentration of Mass Incarceration," Daedalus 139:3, 20–31.

- Run into Kuhl, Krivo, and Peterson.

- Encounter, e.chiliad., David S. Kirk. 2008. "The Neighborhood Context of Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Arrest," Demography 45:1, 55–77.

- Anthony A. Braga. 2015. "Ameliorate Policing Tin Ameliorate Legitimacy and Reduce Mass Incarceration," Harvard Law Review Forum 129, 233–41.

- Robert J. Sampson, Stephen W. Raudenbush, and Felton Earls. 1997. "Neighborhoods and Violent Criminal offence: A Multilevel Study of Collective Efficacy," Science 277, 918–24.

- Sampson 2012.

- Ibid.

- Patrick T. Sharkey. 2006. "Navigating Unsafe Streets: The Sources and Consequences of Street Efficacy," American Sociological Review 71, 826–46, 830.

- Sampson 2012.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- David S. Kirk and Andrew V. Papachristos. 2011. "Cultural Mechanisms and the Persistence of Neigh- borhood Violence," American Journal of Sociology 166:4, 1190–233, 1190.

- Ibid., 1190–233.

- Sampson 2012.

- Keith R. Ihlanfeldt. 2006. "Neighborhood Criminal offence and Immature Males' Chore Opportunity," The Journal of Police & Economics 49:i, 249–83.

- See Matthew T. Lee and Ramiro Martinez Jr. 2009. "Clearing Reduces Offense: An Emerging Scholarly Consensus," Folklore of Crime, Law and Deviance 13, 3–16.

- John M. MacDonald, John R. Hipp, and Charlotte Gill. 2013. "The Effects of Immigrant Concentration on Changes in Neighborhood Offense Rates," Journal of Quantitative Criminology 29:2, 191–215.

- Sampson 2012.

- Robert J. Sampson. 2015. "Immigration and America's Urban Revival," The American Prospect (Summer)

- Leovy.

- Lyndsay N. Boggess and John R. Hipp. 2010. "Violent Crime, Residential Instability and Mobility: Does the Relationship Differ in Minority Neighborhoods?" Journal of Quantitative Criminology 26:3, 351–70.

- Sampson 2012.

- Boggess and Hipp 2010. See also Hipp, Tita, and Greenbaum.

- Johanna Lacoe and Ingrid Gould Ellen. 2015. "Mortgage Foreclosures and the Irresolute Mix of Offense in Micro-neighborhoods," Periodical of Inquiry in Crime and Delinquency 52:5, 1–thirty. See as well Ingrid Gould Ellen, Johanna Lacoe, and Claudia Ayanna Sharygin. 2013. "Do foreclosures cause crime?" Journal of Urban Economics 74, 59–70.

- Lacoe and Ellen.

- David S. Kirk and Derek S. Hyra. 2012. "Dwelling Foreclosures and Community Offense: Causal or Spurious Association?" Social Scientific discipline Quarterly 93:three, 648–70.

- Lin Cui and Randall Walsh. 2014. "Foreclosure, Vacancy and Offense," Periodical of Urban Economics 87, 72–84.

- Matthew Desmond. 2016. Evicted: Poverty and Profit in the American City, New York: Crown Publishers.

- Ibid.

- Jane Jacobs. 1961. The Expiry and Life of Great American Cities, New York: Vintage Books.

- James Thou. Anderson, John M. MacDonald, Ricky Bluthenthal, and J. Scott Ashwood. 2013. "Reducing Crime by Shaping the Built Surroundings with Zoning: An Empirical Study of Los Angeles," University of Pennsylvania Law Review 161, 699–756.

- Michelle Kondo, Bernadette Hohl, SeungHoon Han, and Charles Branas. 2015. "Effects of greening and customs reuse of vacant lots on crime," Urban Studies, 1–17.

- Kirk and Laub.

- Lyndsay N. Boggess and John R. Hipp. 2016. "The Spatial Dimensions of Gentrification and the Consequences for Neighborhood Crime," Justice Quarterly 33:4, 584–613.

- Kirk and Laub. Meet also Amy Ellen Schwartz, Scott Susin, and Ioan Voicu. 2003. "Has Falling Criminal offense Driven New York City'south Real Estate Boom?" Journal of Housing Research fourteen:1, 101–35.

- Hanna Rosin. 2008. "American Murder Mystery," The Atlantic.

- Ingrid Gould Ellen, Michael C. Lens, and Katherine O'Regan. 2011. "Memphis Murder Mystery Revisited: Do Housing Vouchers Cause Crime?", U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Evolution.

- E.g., Leah Hendey, George Galster, Susan J. Popkin, and Chris Hayes. 2016. "Housing Option Voucher Holders and Neighborhood Offense: A Dynamic Panel Analysis from Chicago," Urban Affairs Review 52:4, 471–500.

- Brent D. Mast and Ronald E. Wilson. 2013. "Housing Selection Vouchers and Crime in Charlotte, NC," Housing Policy Debate 23:3, 559–96.

- Susan J. Popkin, Michael J. Rich, Leah Hendey, Chris Hayes, Joe Parilla, and George Galster. 2012. "Public Housing Transformation and Crime: Making the Case for Responsible Relocation," Cityscape 14:3, 137–60.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Xavier de Souza Briggs and Margery Austin Turner. 2005. "Assisted Housing Mobility and the Success of Depression-Income Minority Families: Lessons for Policy, Practice, and Future Research," Northwestern Journal of Law & Social Policy 1:1, 25–61.

- Jason S. Fish, Susan Ettner, Alfonso Ang, and Arleen F. Brownish. 2010. "Association of Perceived Neighborhood Safety on Body Mass Index," American Journal of Public Health 100:eleven, 2296–303.

- Stephen 50. Buka, Theresa L. Stichick, Isolde Birdthistle, and Felton J. Earls. 2001. "Youth Exposure to Violence: Prevalence, Risks, and Consequences," American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 71:3, 298–310.

- James Garbarino, Catherine P. Bradshaw, and Joseph A. Vorrasi. 2002. "Mitigating the Effects of Gun Violence on Children and Youth," The Future of Children 12:two, 73–85.

- Patrick Sharkey, Amy Ellen Schwartz, Ingrid Gould Ellen, and Johanna Lacoe. 2014. "High Stakes in the Classroom, High Stakes on the Street: The Furnishings of Community Violence on Students' Standardized Exam Performance," Sociological Science one, 199–220.

- Julia Burdick-Will. 2016. "Neighborhood Violent Criminal offence and Academic Growth in Chicago: Lasting Furnishings of Early Exposure," Social Forces 95:1, 133–58.

- Raj Chetty and Nathaniel Hendren. 2015. "The Impacts of Neighborhoods on Intergenerational Mobility: Childhood Exposure Furnishings and County-Level Estimates."

- Susan J. Popkin, Mary Bogle, Janine M. Zweig, Priya Saxena, Lina Breslav, and Molly Michie. 2015. "Allow Girls be Girls: How Coercive Sexual Environments Affect Girls Who Live in Disadvantaged Communities and What Nosotros Tin can Exercise about Information technology," Urban Institute.

- See Lauren J. Krivo. 2014. "Reducing Crime Through Community Investment: Tin We Make It Work?" Criminology & Public Policy 13:2, 189–92.

- Sara B. Heller, Anuj K. Shah, Jonathan Guryan, Jens Ludwig, Sendhil Mullainathan, and Harold A. Pollack. 2016. "Thinking, Fast and Slow? Some Experiments to Reduce Offense and Dropout in Chicago," NBER Working Newspaper No. 21178.

- Friedson and Sharkey.

Source: https://www.huduser.gov/portal/periodicals/em/summer16/highlight2.html

0 Response to "Charlotte Police Help Decrease Robberies Agains Hispanics in Apartment Complex"

Enregistrer un commentaire